When Governments Buy Metal, Premiums Move; Strategic Reserves Reshape Physical Metals Pricing

Exploring the far-reaching implications of strategic material stockpiling.

Understanding premiums, discounts and the associated "basis risk" in metals markets.

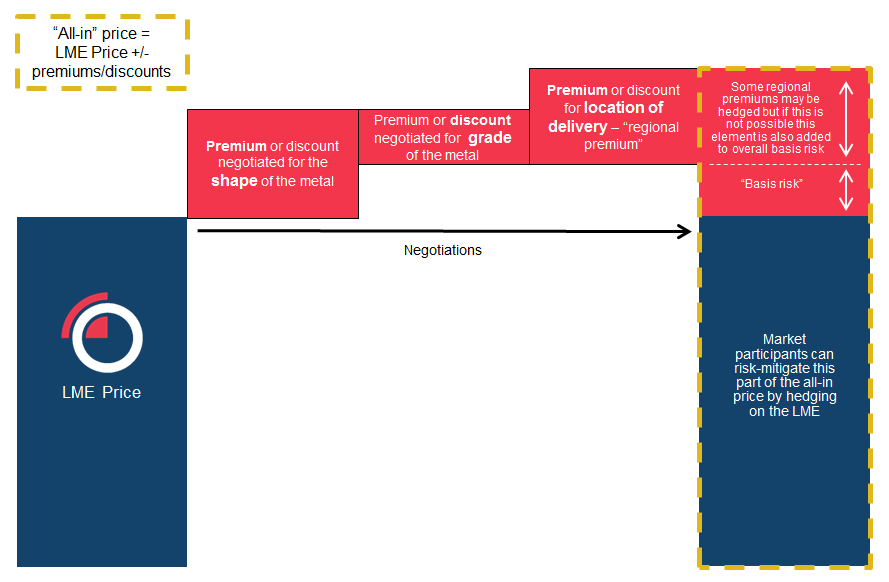

In the article “How are LME reference prices used in physical metals contracts?” we looked at how and why metal prices discovered on the London Metal Exchange (LME) are referenced in physical contracts all along the value chain. In this piece, we consider another element in the pricing and sourcing of industrial metals: “premiums” and “discounts” (and the associated “basis risk”).

Premiums and discounts are the difference a buyer will pay for metal compared to the global reference price. They are negotiated in order to account for the specific characteristics of what metal is being delivered and where.

They exist in metals markets because the global reference price, discovered on the LME, is based on a standardised metal grade and shape. Deviations from this standard of metal need to be reflected in the final price that is paid in the physical market. When negotiating the price of a contract to take delivery of physical metal, buyers and sellers will usually start by referencing the LME price for the underlying material and then negotiate discounts and premiums based on the various factors affecting delivery, as well as the type (brand, shape or quality) of metal being bought or sold.

This is a bit like buying and selling a house. You start with an underlying price based on the overall level of the housing market at that moment in time (for metals the equivalent for this example is the LME reference price) and then the buyer and seller may negotiate the price up or down based on a number of key factors like:

Once these, plus other relevant factors, have been negotiated, the buyer and seller end up with an “all-in” price – the base price adjusted for all the premiums and discounts.

As we have seen, the non-ferrous metals market will negotiate a price that includes 1) a base reference price and 2) a premium or discount portion. And while hedging the base reference price portion on the LME is relatively straightforward, not all of the premium or discount portion can be hedged. The “unhedgeable” portion is called basis risk. Depending on what factors contribute to the all-in price and which of these can be risk-managed (with the financial tools currently available), there is an impact on how much basis risk the buyer and seller may take on (see fig 1).

There are a number of factors that are considered during the negotiation of a metal contract that will lead to premiums and discounts. These include, but are not limited to:

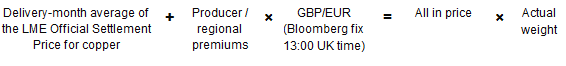

A simplified typical transaction for LME-grade copper in Europe could be priced along these lines:

Some markets announce premiums once a year during “mating season” – the period between LME Week in autumn and the New Year (e.g., copper producer premiums), whilst other industries negotiate once every three months (e.g., aluminium Japanese premiums).

Market participants can often directly reference premium prices from price reporting agencies (PRAs) who themselves survey a broad sample of both buyers and sellers of metal to come up with an independent price index for the market.

In the copper market, where producers may offer fixed annual premiums, the annual premium may be priced higher than a day-to-day premium, given the higher price-risk exposure of the producer offering an annual fixed price. In times of copper oversupply, when premiums may be expected to decrease, customers will typically buy 20-30% of the physical metal they need on an annual basis and over 75% in times of undersupply when premiums are at risk of moving higher.

The non-ferrous metals industry has evolved to carefully risk-manage most aspects of a physical contract by splitting out the elements that create the all-in price. For example, the underlying metal’s reference price can be hedged on the LME or over the counter (OTC). This differs from the steel industry which still heavily relies on bilateral negotiations of an all-in price for a specific product and inclusive of all fees, premiums, discounts, allowances for VAT and other charges. These bilateral negotiations are often informed by referencing index prices for very specific material types published by PRAs.

For some non-ferrous metals, the regional part of a premium, i.e., where the buyer wants to take delivery, has evolved into a market that is traded daily. Regional premium price levels are often agreed upon during bilateral physical contract negotiations, sometimes referencing or contributing to a PRA premium benchmark.

Pricing of regional premiums can be affected by factors relating specifically to the region in question ranging from geopolitics and the weather through to insurance and freight-rate fluctuations. In 2005, for example, Hurricane Katrina effectively reduced the regional premium for zinc in New Orleans to $0 overnight due to difficulties in getting metal out of New Orleans, as well as the metal becoming contaminated.

Politics and local policy also play a role. Back in 2018 the global aluminium market was responding to President Trump’s update to the US Department of Commerce’s Section 232 policy – where a 10% tariff was to be applied to US aluminium imports – by pricing this into the regional premium. The effects of this are complicated by the fact that certain countries and trading blocs are exempt from paying the tariffs.

In some markets the basis risk between stages of production and the historical reference price has increased to levels where the benefits of hedging may be outweighed by the remaining basis-risk exposure.

In the steel industry, for example, there has never been a globally accepted central reference price for all steel products. However, the market is evolving and employing more hedging strategies, thus requiring more financial instruments to do so. To complement the success of the original launch of LME steel scrap and rebar contracts in 2015 and of iron ore contracts on other exchanges, the LME introduced a suite of hot-rolled coil (HRC) contracts to allow companies in the flat steel value chain to hedge the bulk of their price risk exposure.

Premiums have evolved to reflect the physical nature of metals markets. The way in which they are discovered and used varies between different metals markets based on how participants wish to mitigate their price risk.

Stay connected with our latest developments. Share your details to receive updates and analyses from LME Insight.